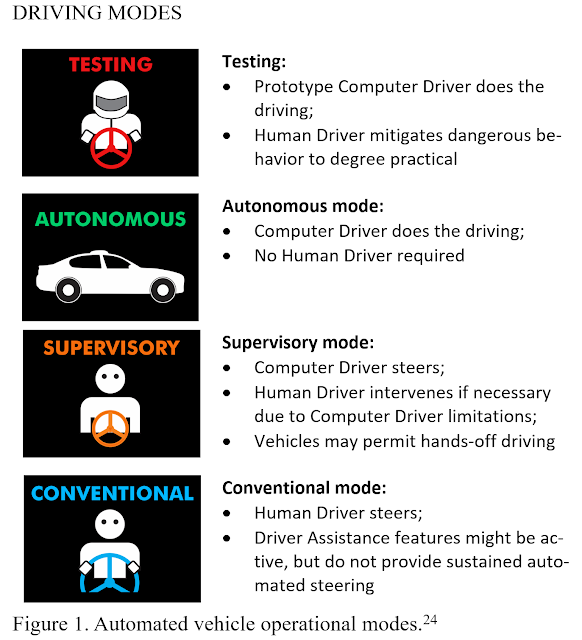

We should formally define SAE Level 2+ to be a feature that includes not only Level 2 abilities but also the ability to change its travel path via intersections and/or interchanges. Level 2+ should be regulated in the same bin as SAE Level 3 systems.

There is a lot to unpack here, but ultimately doing this matters for road safety, with much higher stakes over the next 10 years than regulating completely driverless (Level 4/5) robotaxi and robotruck safety. Because Level 2+ is already on the roads, doing real harm to real people today.

First, to address the definition folks who are losing it over me uttering the term "2+" right now, I am very well aware that SAE J3016 outlaws notation like "Level 2+". My suggestion is to change things to make it a defined term, since it is happening with or without SAE's blessing, and we urgently need consistently defined term for the things that everyone else calls Level 2+ or Level 2++. (Description and analysis of SAE Levels here. Myth 5 talks about Level 2+ in particular.)

From a safety point of view, we've known for decades that when you take away steering responsibility the human driver will drop out, suffering from automation complacency. There have been enough fatalities from plain features said to be Level 2 (automated lane keeping + automated speed), such as cars under-running crossing big rigs, that we know this is an issue. But we also have ways of trying to address this by requiring a combination of operational design domain enforcement and camera-based driver monitoring. This will take a while to play out, but the process has started. Maybe regulatory intervention will eventually resolve the worst of those issues. Maybe not -- but let's leave that for another day.

What's left is the middle ground between next-gen-cruise-control features (lane centering + automated speed) and vehicles that aspire to be robotaxis or robotrucks but aren't quite there. That middle ground includes a human driver so the designers can keep the driver in the loop to avoid and/or blame for crashes. If you thought plain Level 2 had problems with automation complacency, Level 2+ says “hold my beer.” (Have a look at the concept of the moral crumple zone. And do not involve beer in driving in any way whatsoever.)

Expecting a normal human being to pay continuous hawk-like attention for hours while a car drives itself almost perfectly is beyond credibility. And dangerous, because things might seem fine for lots and lots of miles — until the crash comes out of the blue and the driver is blamed for not preventing it. Telling people to pay attention isn’t going to cut it. And I really have my doubts that driver monitoring will work well enough to ensure quick reaction time after hours of monotony.

People just suck at paying attention to boring tasks and reacting quickly to sudden life-threatening failures. And blaming them for sucking won’t stop the next crash. I think the car is going to have to be able to actively manage the human rather than the human managing the car, and the car will have to ensure safety until the human driver has time to re-engage with the driving task (10 seconds, 30 seconds, maybe longer sometimes). That sounds more like a Level 3 feature than a Level 2 feature from a regulatory point of view.

Tesla FSD is the poster child for Level 2+, but over the next 5 years we will see a lot more companies testing these waters as they give up on their robotaxi dreams and settle for something that almost drives itself -- but not quite.

The definition I propose is Level 2+ is a feature that meets the requirements for Level 2 but also is capable of changing roadways at an intersection and/or interchange.

Put simply, if it drives you down a single road, it's Level 2. But if it can make turns or use an exit/entrance ramp it is Level 2+.

One might pick different criteria, but this has the advantage of being simple and relatively unambiguous. Lane changing on the same roadway is still Level 2. But you are at Level 2+ once you start doing intersections, or go down the road (ha!) of recognizing traffic lights, looking at traffic for unprotected left turns, and so on. In other words, almost a robotaxi -- but with a human trying to guess when the computer driver will make a mistake and then potentially getting blamed for a crash.

No doubt there will be minor edge cases to be clarified, probably having to do with the exact definition of “roadway”. Or someone can propose a good definition for that word that takes care of the edge cases. The point here is not to write detailed legal wording, but rather to get the idea across of making turns at an intersection being the litmus test for Level 2+.

From a regulatory point of view, Level 2+ vehicles should be regulated the same as Level 3 vehicles. I realize Level 2+ is not necessarily a strict subset of Level 3, but the levels were never intended to be a deployment path, despite the use of a numbering system. I think they both share a concern of adequate driver engagement when needed in a system that is essentially guaranteed to create driver complacency and slow reaction times due to loss of situational awareness.

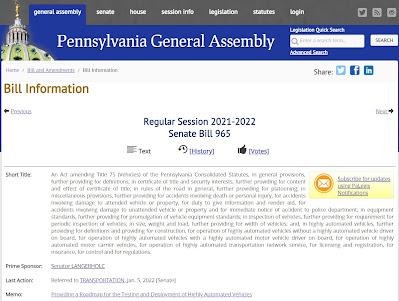

How does this look in practice? In the various bills floating around federal and state legislatures right now, they should include a definition of Level 2+ (Level 2 + intersection/interchange capability) and group it with Level 3 for whatever regulatory strategy they propose. Simple as that.

If SAE ORAD wants to take up this proposal for SAE J3016 that's fine too. (Bet some committee members are reading this — happy to discuss at the next meeting if you’re willing to entertain it.) But that document disclaims safety as being out of its scope, so what I care about a lot more are the regulatory frameworks that are currently near-toothless for the not-quite-robotaxi Level 2+ features already being driven on public roads.

Note: Based on proposed legislation I've seen, pulling Level 2+ into the Level 3 bin is the most urgent and viable path to improve regulatory oversight of this technology in the near to mid term. If you really want to do away with the levels I have a detailed way to do this, noting that the cut-line for Supervisory is at Level 2 rather than Level 2+, but is otherwise compatible with this essay. If you want to use the modes but change the cut line, let’s talk about how to do that without breaking anything.

Note: Tesla fans can react unfavorably to my essays and social media posts. To head off some of the “debate” — yes, navigate-on-autopilot counts as Level 2+ in my view. And we have the crashes to prove it. And no, Teslas are not dramatically safer than other cars by any credible analysis I’ve ever seen.