Coverage of Lucid software problems (cars bricked; wrong direction of travel) might be written off to growing pains for a new company. But I think this is just yet another story about a deeper industry-wide problem. (The article notes other more established companies have problems too.) This weeks story: https://www.businessinsider.com/electric-vehicle-startup-lucid-struggling-production-reveal-insiders-owners-2022-11

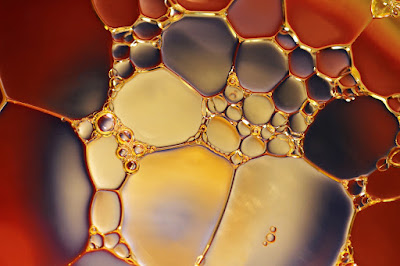

mix as oil and water.

All software is not created equal. For cars I am seeing three types:

- Shiny Infotainment and other software that provides shiny customer features might be less reliable and still sell cars. There are limits to tolerance for problems, but more forgiveness if the features are shiny enough. Apparently "coding" is enough to build valuable companies, as is slapping "beta" on the label as a pretext for further reducing quality expectations for a product sold retail. Maximizing lines of code per day has made lots of founders rich.

- Critical deeply embedded control firmware has to be rock solid or you're going to get serious malfunctions. "Coding" without software engineering invariably leads to deeper problems, some of which feature in harm to people. Maximizing lines of code per day at the cost of impaired quality and skipped safety engineering practices has made customers dead.

- "AI" software based on machine learning, which is being asked to do safety critical work but often without using the foundational skills and processes of the critical software experts.

Journalists should differentiate when reporting. If you must call a shiny software problem a "glitch" so be it. But critical software failures are due to *defects* reflective of an important lapse in engineering, not glitches due to being in a hurry to deploy the new hotness.

Companies get in trouble, sometimes very seriously, via several mechanisms:

- Treating all software the same. Software needs to be thought of as either shiny or critical. They are as oil and water. (Maybe this could be different, but in the world we live in this is the only pragmatic approach.)

- Treating "software staff" as fungible. Developers for shiny vs. critical software are deeply different. The skill sets, mindset, and work flows are quite different. So is the training required. While some can do both, few can do both well. (This is not about being "smart." It is about being different.) To a first approximation, anyone talking about "coding" is in the shiny software business, especially if they indicate that knowing how to code is equivalent to being a software engineer.

- Mixed components and features. We see an endless parade of NHTSA recalls for malfunctioning backup cameras. The usual story is that a critical function (backup camera; by definition safety critical per FMVSS) is hosted on a platform optimized for shiny (infotainment display and OS). The only surprise is that car companies persist in thinking that plan will work out well.

- We're still sorting out how to fit AI software into the mix. A lot of that will end up forcing a choice between the shiny bin or the critical bin, with a human/machine interface suitable to the choice. Making AI software shiny can be a reasonable choice -- but only if we don't pretend shiny AI it is fit for purpose as critical software. (Critical machine learning might be done, but there is a significant gap to overcome in skills, work flows, etc. that the industry is only beginning to wrestle with.)